Symphonic Sting showed that he doesn't need symphony orchestras...

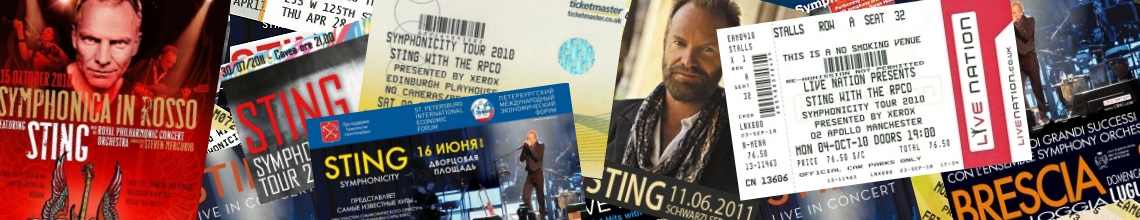

A Bauhaus-style stage, moving light panels, London's Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. A bombastic spectacle. But when the main character of the whole circus, Sting (58), sang the last encore a cappella, it was clear that he could easily do without all that.

The idea of being on the O2 Arena stage alone, with just a microphone and perhaps an acoustic guitar, is much more seductive than the detailed mega-show of the 'Symphonicities' album tour.

I had a similar feeling the last time I was on Leonard Cohen's "farewell" tour. His backing band tried wholeheartedly to wrap every second of the concert in an impenetrable candy-candy crust, but when Cohen sang alone, it suddenly didn't matter. It was clear that he had something to say; and that he would push the power of his authorial and singing personality through even the most rosy hell. I just had the feeling that the band was given to him as a punishment, so that he could fight with it... I thought the same thing about Sting's performance.

Of course, the question arises why an author and singer of Sting's stature needs to add orchestral arrangements to his songs. Apparently, there is nothing behind this other than the desire for "big sound and big show" - the age-old desire to confirm that even pop music can aspire to the title of high art.

Pop music has of course shown many times that it can. But it has never been because it wears other people's feathers and covers itself with a coat of seriousness, moreover, sewn in such a way that a more attentive observer realizes that the tailor sometimes does not know where to go and which of the two gentlemen to take the measure.

Sting's album, on which we find the basis of the repertoire of the current tour, i.e. a dozen famous numbers in orchestral arrangements, is called 'Symphonicities' - apparently because a symphony orchestra plays on them. They have nothing in common with the form of a symphony, like all possible albums of the Symphonic Beatles, Symphonic Queen, Symphonic Pink Floyd type.

These are ordinary songs that were once hits and so it is necessary not to spoil them too much when arranging them for an orchestra and not to take away their humming potential. Underlined, cut: useless work of hired (albeit this time really famous) Bauer organists eager to grab a little of that fame.

What is much worse is that the authors and (in Sting's case) commissioners of similar arrangements ignore one of the most important aspects of non-serious (fun) music: much more than the composer's originality, an engaging sound, authenticity and experience are valued in pop and rock. Sting in Police showed how economical means jazzmen can succeed on the new wave scene, the aforementioned Cohen, whose top album 'I'm Your Man' sounds as if it was recorded on a turntable by Eva and Vašek, with his expression all the kitsch and futility of the people; the boilermaker's mumbling and the thunderous harmonica of Bob Dylan do not matter, because we feel that the man has something to say.

If you add an orchestra, all this magic is ruined. The orchestra cannot spontaneously let loose, and at the same time it plays something that is not its own. Everyone is groping on the same boat, the construction of which definitely does not promise a safe arrival.

Sting, who uses the economical, but all the more sovereign playing of jazz aces on his studio albums, insured himself at concerts. The symphonists were also preceded by a backing band: a guitarist, a bassist, two drummers and a charming singer. When the orchestra - for example in 'When We Dance' - took a few bars of pause, this band sounded alone and was charmingly fragile. Being on stage with only five supporting musicians but the stars of the entire program probably didn't seem attractive enough, although I'm sure the audience would have reached the same number. They would only have missed out on a few brilliant solos by the trumpet, clarinet, violin and cello.

According to the program, Robert Molnar's set was inspired by Bauhaus. The illuminated plinth on which the orchestra stood and the trio of moving light and projection panels above the performers' heads at least showed that there is strength in simplicity and gave a kind of pre-war avant-garde impression - when they were not being played by the unimaginative video art of "ten inspiring artists we approached".

The orchestra moved quite characteristically in these backdrops: its synchronized jumps and Mexican waves, as well as its sweet playing and occasional Latin rhythms, most of all reminded us of the promenade bodies in the gazebos of spa resorts. Which is actually somehow part of the point; entertaining jazz orchestras and the artistic avant-garde are contemporaries who lived side by side in a contented symbiosis.

The orchestral arrangements of the songs that were performed at the concert were mostly in the spirit of decent undertones; the orchestra intervened more dramatically only a few times, most often in the form of solos. The worst scars were suffered by 'Every Breath You Take': pleasant strings in the introduction, the rhythm that only sets in after the first verse, a truly "symphonic" climax... Coming up with a worse idea would already smack of genius.

The Russians, who did not forget to paint the stage red, achieved a truly dark and dramatic arrangement, which somehow did not correspond to the fragile melody of Sting's singing. The most fun "transformation" was the song 'Moon Over Bourbon Street' - a creeping orchestration, visual and sound references to classic silent horror, Sting's genre-essential theremin solo, a favourite toy for creating cinematic tension.

The remaining two dozen numbers were simply great to listen to. The orchestra did not spoil them or elevate them to heights. It simply played something and Sting, singing as confidently as on the records in front of him with the band on his sides, showed his mastery. The two units did not bother each other.

I believe that a similar combination could not have turned out better.

© Aktuálne by Petr Ferenc

09222010

SET LIST

- If I Ever Lose My Faith In You

- Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic

- Englishman In New York

- Roxanne

- Straight To My Heart

- When We Dance

- Russians

- I Hung My Head

- Shape Of My Heart

- Why Should I Cry For You?

- Whenever I Say Your Name

- Fields Of Gold

- Next To You

- A Thousand Years

- This Cowboy Song

- Tomorrow We'll See

- Moon Over Bourbon Street

- End Of The Game

- You Will Be My Ain True Love

- All Would Envy

- Mad About You

- King Of Pain

- Every Breath You Take

- Desert Rose

- She's Too Good For Me

- Fragile

- I Was Brought To My Senses